Earlier this month, as I drove past the spot where Benazir Bhutto was assassinated on Murree Road near Liaquat Garden in Rawalpindi on December 27, 2007, I thought of how much had happened since that tragic evening. She had returned, against the advice of many friends, to a violent and fractious Pakistan because she felt that her presence was key to the restoration of democracy in her homeland. I knew that road well. Decades earlier I used to turn there on to College Road, on my way to the neighboring Gordon College. Many of Gordon College student demonstrations for democracy in 1968 crashed into the police barricades at that spot.

Those were Halcyon Days compared to what Pakistan is now going through. A year after her much-foretold death, Ms. Bhutto’s Pakistan is wracked by political turmoil and economic uncertainty. It is relying on the world to bail it out again. Yet the answers to its problems lie inside Pakistan. Unless Pakistan settles the wars within and coalesces around its political center, it faces a bleak future and risk of foreign intervention. This is the challenge facing its fledgling civilian government. The world must help it succeed.

Today, Pakistan is run by civilians. But the parliamentary system that had been hijacked by the military ruler, General Pervez Musharraf, and converted into a presidential one remains unchanged. Power continues to flow not from the Prime Minister but from the President. Ms Bhutto’s signed compact (Charter of Democracy) with the other leading party of former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif that called, among other things, for the complete restoration of the judiciary has been shredded. The coalition of her center-left Pakistan Peoples’ Party with Sharif’s center-right Pakistan Muslim League (N) is no more, partly as a result of the time bombs that General Musharraf planted when he brought the PPP into power under political deals that wiped clean all charges against its leadership and by removing the top layer of the judiciary in November 2007 for the second time in one year. The PPP fears that a restored judiciary under the former Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhary would overturn many of those deals creating chaos. Mr. Sharif refuses to compromise on this issue. The PML (N) controls the Punjab, Pakistan’s economically powerful province. The PPP has the center. This standoff threatens the political stability of the country.

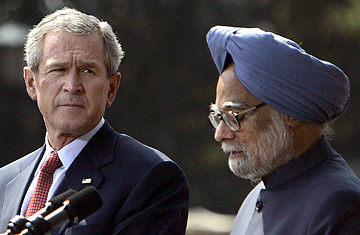

President Asif Ali Zardari, who inherited the political mantle of his wife, Ms. Bhutto, has continued the Musharrafian alliance with the United States against the terrorists and militants that threaten Pakistan’s Federally Administered Tribal Areas bordering Afghanistan and increasingly are operating in the hinterland. He also continued the Musharraf policy of making peace overtures to neighboring India and offered even to forego a first nuclear strike in case of a conflict between the two rivals. But, despite his attempt at producing a consensus among the political parties in parliament against terrorism, most parties on the right wing of the political spectrum have started backing away from that stance. And the recent Mumbai terror attacks that are being linked to Pakistani militant groups have brought India and Pakistan to the edge of another conflict.

The economy is still in tatters. Distracted by political wrangling soon after the February 2008 elections, the new government failed to concentrate on the rapidly deteriorating economic situation until late in the year. The spike in global fuel and food prices added to its woes. Foreign exchange reserves have plummeted from a height of $16 billion to close to $4 billion. Food prices are up nearly 50 percent. Energy and water shortages persist. A program with the International Monetary Fund, once pronounced anathema by Mr. Zardari, is now in force. And Pakistan is holding its collective breath for the countries that it calls "Friends of Pakistan" to actually come forward with vast amounts of financial aid. Absent a robust and growth-oriented economic program and an improved security situation, such aid may not be forthcoming. These countries will likely wait for the IMF program to take root. Donors are also wary of dealing with a sprawling government of some 60 cabinet members, most of whom are eminently unqualified for their respective tasks, and represent parochial interests rather than a cohesive central policy.

On the security front, 2008 may prove to be as violent as 2007, when nearly 60 suicide bombings took place inside Pakistan, most against the armed forces. Adding to the volatile mix is the re-emergence in force of the Punjabi Sunni militant groups such as the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi and the Lashkar-e-Tyaba that even threaten the state that once sponsored their help for the Kashmiri Mujahideen. The army, overstretched in the region bordering Afghanistan, cannot be deployed in a major operation inside Punjab. Without army action, these groups will continue to flourish. There is no police force worth the name that could be used in controlling these elements and de-weaponizing Pakistani society. More important, there is no public debate on what sort of society Pakistanis want to create over 61 years after becoming an independent state. Nor is there any sign of such a debate taking place in the near future.

Now, with India increasing the pressure on Pakistan to act against the militants that India alleges were behind the Mumbai attacks, and garnering international support for that cause, Pakistan faces the possibility of military action on its eastern frontier. If that happens, the Pakistan army will be thrust once more into the political vortex. Then, if the political center does not hold, history may well repeat itself and the army may be "asked" by the people to take charge once again. If that happens, Ms. Bhutto will have died in vain.

This piece appeared in The Washington Post Post Global on 26 December 2008