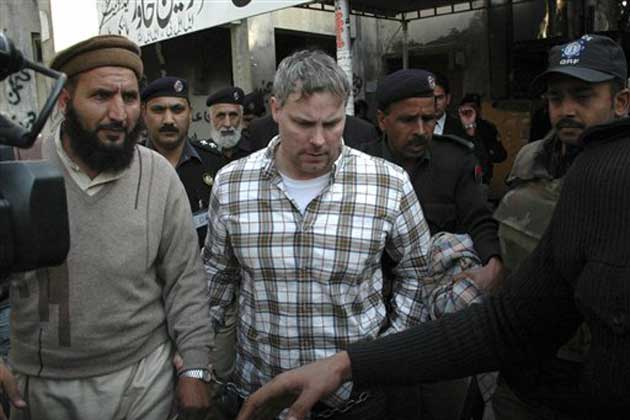

Behind all the talk of a strategic dialogue and strategic partnership between the United States and Pakistan lurks the reality of a persistent transactional relationship, based on short-term objectives that intrude rudely into the limelight every time a drone attack kills civilians inside Pakistan or in the instance when an American “operative” is caught by the Pakistanis after killing two people on the streets of Lahore.

In “Paranoidistan,” as the historian Ayesha Jalal has called Pakistan, the public and the authorities are prepared to believe the worst. Conspiracy theories abound, involving the C.I.A., Israel and India, in various permutations.

So, it is not surprising that the Raymond Davis case has left mistrust in its wake. Unanswered questions abound: What was he doing driving alone in an unmarked car in the heart of Lahore’s bazaar district? Why did he shoot to kill two youths, and then step outside his car to finish them off, and photograph them again? And why was he photographing religious seminaries and bunkers, as leaked Pakistani information indicates?

Apart from allowing the extremist Pakistani right-wingers to capture the public space with their anti-American propaganda, this case left the Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate embarrassed and angry. And it has sent friends of the United States into sullen silence. Then, as soon as Davis was released in a shadowy deal involving “blood money,” came the drone attack on Datta Khel in the border region of Pakistan that killed some 40 people.

Senior Pakistani military and intelligence officials maintain this was a “normal” jirga of peaceful tribesmen. U.S. officials say that it was designed to fool the C.I.A. and that the real purpose of the open-air gathering was to conduct business harmful to the coalition’s interests in Afghanistan. Regardless, the Pakistani army chief, Gen. Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, cut whole categories of U.S. military personnel based in Pakistan and privately warned the U.S. that he will “react” if the attacks continue. His intelligence chief, Lt. Gen. Ahmed Shuja Pasha, recently in Washington to discuss the issue with his C.I.A. counterpart, echoed that hard line. Hence, the report of a senior military official raising the possibility of shooting down the drones.

The Pakistani military and government do cooperate with the C.I.A. and U.S. military in the border region, but they will not acknowledge this openly. Both countries need to address their concerns frankly and in detail rather than continue a charade that misinforms their own people about what they are doing and why.

The United States needs to stop paying the Pakistan army with coalition support funds to fight in the border region and instead provide it adequate military aid in kind, as part of a carefully structured cooperative program to build its mobility and firepower against the militants.

Money cannot buy love. It is more likely to generate contempt among the rank and file of the Pakistani military. If the ultimate objective is to stabilize Afghanistan and Pakistan, then economic and peaceful political means, and talks with the militants to bring them into the fold of normal political discourse, are also needed. Not drone attacks. Nor trigger-happy cowboys in the heartland of Pakistan.

Shuja Nawaz is director of the South Asia Center at the Atlantic Council. This essay is part of the New York Times "Room for Debate" on "When Pakistan Says No to the CIA," and includes pieces by C. Christine Fair, Bruce Riedel, Mark Quarterman, Cyril Almeida, Reza Nasim Jan, and Reuel Marc Gerecht.