A panel discussion at the US Institute for Peace with Faiysal Ali Khan, Shuja Nawaz, Jim Bever, and Rick Barton. Organized jintly by CSIS and USIP. February 3, 2009

http://pomed.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/pomed-notes_usip_2_3_09.pdf

A panel discussion at the US Institute for Peace with Faiysal Ali Khan, Shuja Nawaz, Jim Bever, and Rick Barton. Organized jintly by CSIS and USIP. February 3, 2009

http://pomed.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/pomed-notes_usip_2_3_09.pdf

Commentary on the Council for Foreign Relations website on February 5, 2009

http://www.cfr.org/publication/18472/pakistans_fickle_war.html?breadcrumb=%2Fissue%2F135%2Fterrorism

Shuja Nawaz, director of the Atlantic Council’s new South Asia Center, commented today for an NPR piece on President Obama’s use of unmanned drone strikes in Pakistan’s tribal regions.

Other commentators included Stephen Cohen of the Brookings Institution’s Foreign Policy Studies program; Retired Army Col. Andrew Bacevich, a professor of history and international affairs at Boston University; and Seth Jones, a South Asia expert at RAND Corporation.

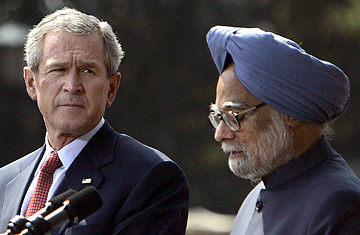

Photo credit: Maya Alleruzzo, AP, NPR.

Shuja Nawaz, director of the Atlantic Council’s new South Asia Center, was interviewed today with Hisham Melhem by Michel Martin for NPR’s Tell Me More. They discussed the significance and impact of President Obama’s decision to conduct his first interview with Al-Arabiya, a news channel based in Dubai.

Photo credit: AP Photo.

Quoted in Washington Post story January 24, 2009

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/01/23/AR2009012304189.html

Although it may surprise many insular people in the United States, the people of Iraq and Afghanistan and the region they inhabit want nothing more than what most Americans dream of. They want peace, a chance to raise their children with good healthcare and education, and an ability to earn a decent living. They do not want to be invaded or occupied, nor ruled with an iron fist. Decades of war have damaged Afghanistan and Iraq and destroyed the fabric of their societies. Their intellectuals and middle class have either been targeted by internal militancy or have left to seek a better life, ironically in the United States and the West, the occupying force and source of their current discomfiture.

The best hope for the people of Iraq and Afghanistan from the new US administration that took office yesterday is that it will set in motion plans for a military exit but launch a sustained assault on poverty and help inoculate both countries against the rise of autocratic systems of rule. Both are tribal societies with centuries-old traditions and mores. Devolving power to the provinces and districts and to local councils and encouraging the formation of a national consensus along the lines of the previously stable “Meesak-i-milli” (People’s Concord) of Afghanistan will be one way to assure stability. Start rebuilding socio-political structures from the bottom up not top downward.

But a US military withdrawal must not mean a political or economic exit from both countries, the worst nightmare of the people of both war-torn lands. The US abandoned Afghanistan once before, after the Soviets left in 1989. In the words of General Brent Scowcroft, it had to go back in 2001 to complete the job that it ought to have done at that time. It also left Iraq to its own devices after the liberation of Kuwait in 1991. It cannot risk making the same mistake again. For there are broader implications of such actions.

To enhance regional harmony, the new US President will also need to build better and longer relationships with both countries’ neighbors: re-open dialog with Iran instead of painting it into a hostile corner, and build a longer-term relationship with the people of Pakistan rather than with any single ruler or autocrat. This will restore stability in the region and allow Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan to contribute towards peace rather than war in one of the most dangerous neighborhoods of the world today. If they could, the people of Iraq and Afghanistan would vote for a US president who waged peace not war.

Shuja Nawaz is director of the South Asia Center at the Atlantic Council. An edited and translated version of this piece ran in Foreign Policy Edición Española.

Shuja Nawaz, director of the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center, published a piece in Foreign Policy Edición Española entitled “AFGANISTÁN E IRAK NECESITAN UNA OFENSIVA CONTRA LA POBREZA.” A longer, English language version appears in New Atlanticist as “Fulfilling Iraqi and Afghan Dreams and Wishes.”

The full text of the original appears below as a courtesy to Council members.

El nuevo presidente estadounidense tendrá que forjar unas relaciones mejores y más duraderas con los vecinos de Irak y Afganistán [1], así como llevar acabo una retirada militar que no implique un abandono económico y político de unos países destrozados por la guerra.

Aunque quizá sorprenda a mucha gente que se aísla en Estados Unidos, los habitantes de Irak y Afganistán, así como de la región en la que se encuentran, no quieren más que lo que anhelan la mayoría de los estadounidenses: paz, una oportunidad para criar a sus hijos con buena sanidad y buena educación, y la capacidad de ganarse la vida decentemente. No quieren ser invadidos ni ocupados, ni que los gobiernen con mano de hierro. Decenios de guerra han hecho daño a Afganistán e Irak y han destruido el tejido de sus sociedades (sus intelectuales y su clase media han sido blancos de la militancia interna o se han ido en busca de una vida mejor, irónicamente a EE UU y Occidente, la fuerza ocupante y fuente de su turbación actual).

La esperanza que pueden tener los pueblos iraquí y afgano respecto al nuevo inquilino de la Casa Blanca es que ponga en marcha planes para una salida militar pero que emprenda una ofensiva sostenida contra la pobreza y ayude a vacunar a los dos países contra el ascenso de sistemas de gobierno autocráticos. Ambos países son sociedades tribales con tradiciones y costumbres que se remontan siglos atrás: una forma de asegurar la estabilidad será traspasar el poder a provincias y distritos y a los consejos locales, y fomentar la formación de un consenso nacional del tipo del antes estable Meesak-i-milli (Concordia del pueblo) de Afganistán. Habrá que empezar a reconstruir las estructuras sociopolíticas de abajo a arriba, no de arriba a abajo.

| Construir una relación a largo plazo con el pueblo de Pakistán, y no con un gobernante o autócrata específico | ||||||

Ahora bien, una retirada militar de Estados Unidos no debe significar una salida política ni económica, la peor pesadilla para la gente de estos dos países desgarrados por la guerra. Estados Unidos ya abandonó Afganistán una vez, después de que se fueran los soviéticos en 1989. En palabras del general Brent Scowcroft, Washington tuvo que volver en 2001 para completar la tarea que debería haber hecho entonces. Asimismo, dejó que los iraquíes se las arreglaran solos tras la liberación de Kuwait en 1991. No puede arriesgarse a volver a cometer el mismo error porque esas acciones tienen repercusiones más amplias.

Para aumentar la armonía nacional, el nuevo presidente estadounidense también tendrá que forjar unas relaciones mejores y más duraderas con los vecinos de ambos Estados: reabrir el diálogo con Irán en vez de arrinconarlo de forma hostil y construir una relación a largo plazo con el pueblo de Pakistán, y no con un gobernante o autócrata específico. Estas medidas restaurarán la estabilidad en la región y permitirán que Irak, Afganistán, Irán y Pakistán contribuyan a la paz, en vez de a la guerra, en una de las zonas más peligrosas del mundo actual. Si pudieran, iraquíes y afganos votarían a un presidente estadounidense que haga la paz, y no la guerra.

Shuja Nawaz, the director of the Atlantic Council’s brand new South Asia Center, appeared on Indian television network NDTV’s 24 x 7 broadcast “The Big Fight” on the subject “What will President Obama mean for India?“

Other participants included Amb. Frank Wisner, Indian fund raiser for Hillary Bal G. Das in New York and Congressman Jim McDermott. The host was NDTV’s CEO Vikram Chandra.

On January 12, 2009 Shuja Nawaz started as the first Director of the new South Asia Center of the Atlantic Council of the United States in Washington DC.

For details visit

http://acus.org/event_blog/shuja-nawaz-direct-south-asia-center-atlantic-council

He can be reached at [email protected]

Charles Dickens called Washington a “city of magnificent intentions.” When Barack Obama takes over on January 20th as the 44th President of the United States, he will need to translate his own lofty ideas into realities. What makes the challenge bigger for him is that he may also be carrying another title: the first globally-elected President of the United States. Unlike any other presidential election in US history, his nomination was favored by denizens of over 90 countries worldwide. All his supporters, here and abroad, expect him to transform the image and reality of the United States, in short order. While this is a daunting task, it also offers him a grand opportunity to make some bold decisions and set the United States and its partners on a fresh path, where an engaged and principled US foreign policy based on humanity and justice would be the rule.

Expectations are high and no where more than in the Muslim World that has seen the past decade marked by a threatened Clash of Civilizations between it and the West. That is also where the most dangerous shoals of foreign policy exist: Gaza, Iraq, Afghanistan, and South Asia, particularly Pakistan, which may be his greatest nightmare.

President Obama will not have much time to tackle each and all of these regions of unrest before he runs out of the hope and goodwill that will support him in his early days in office. The economic detritus of the Bush Administration has made the transition complex and difficult. But certain principles that are already reflected in some of his public statements may help point to likely actions that will allow him to make some historic leaps and take his supporters and doubters both with him.

Here are some things he could in his first 100 days:

President Obama can make this statement more effective by choosing to deliver his major foreign policy speech abroad, preferably in the Muslim World…then see the wave of support carry him over the obstacles to these Grand Objectives.

Where would be a good venue for this event? How about the Wagah border crossing between India and Pakistan, so both Indian and Pakistani crowds can see and hear him? And let those metal gates that are shut by goose-stepping soldiers every evening remain open forever after that as a symbol of good neighborhood and out of respect for a brave new U.S. president who is unafraid to tackle the hardest tasks first.

This piece also appeared on The Huffington Post and on the Atlantic Council website www.acus.org, where the author is now Director, South Asia Center.