"Over the years, I’ve repeatedly made clear that we would take action within Pakistan if we knew where bin Laden was. That is what we’ve done. But it’s important to note that our counterterrorism cooperation with Pakistan helped lead us to bin Laden and the compound where he was hiding. Indeed, bin Laden had declared war against Pakistan as well, and ordered attacks against the Pakistani people."

With those words, President Barack Obama acknowledged Pakistan’s role in the killing of Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad, a military cantonment, in a house that lay half a mile or so from the Pakistan Military Academy. It is unclear why, if Pakistani intelligence had the leads, it would not or could not follow up itself and do the job.

At a time when United States-Pakistan relations are going south in a hurry over aid, Afghanistan, and U.S. intelligence operations inside Pakistan, bin Laden’s death leaves more questions on the table than answers. How could four U.S. helicopters operate some 120 miles inside Pakistani territory and three of them exit without being detected? Were they allowed to do so? And by whom? Or was it Pakistan’s inability to intercept them that allowed the U.S. raid to proceed without a hitch? Clearly the civilian government was first informed when President Obama spoke with President Asif Ali Zardari after the operation was over. If Zardari’s military was in the know, and he was not, this speaks volumes about the internal distrust within Pakistan’s establishment. So far, it appears the United States kept the Pakistan military in the dark. What may be more troubling for the U.S. side is the likelihood that elements of the Pakistani establishment were aware of bin Laden’s presence in Abbottabad and kept it hidden. However remote a possibility this may seem, this question will be asked in Washington D.C. in the weeks to come.

American boots on the ground are much more serious in terms of invasion of Pakistan’s territory and disregard for its sovereignty than the remote drone attacks that have so angered Pakistani officials and politicians lately. The Pakistani military’s official reaction to the death of bin Laden will be telling. If this operation was carried out in close cooperation with the United States, then the trajectory of this declining relationship may be reversed. If not, then the velocity of the decline will increase at a time when the mood in Washington seems to be shifting to black toward Pakistan, on the Hill and also in parts of the Obama administration.

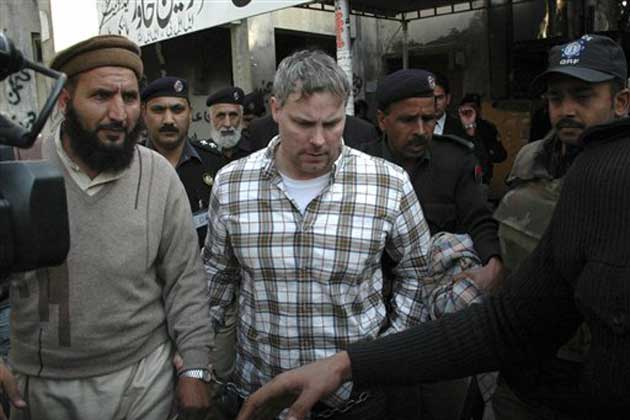

The Strategic Dialogue that was bringing the United States and Pakistan to the table to focus on common objectives has been suspended for now. Both sides are attempting to revive the relationship after the imbroglio over Raymond Davis and the C.I.A.’s operations inside Pakistan. The Pakistanis demand respect. So does the United States. Neither side should try to pull a fast one over the other. They are codependent in the fight against militancy and terror: the United States in trying to exit Afghanistan in an orderly fashion, Pakistan in trying to contain its internal insurgencies. The stakes may be higher for Pakistan since it remains captive of its geography and heavily tied to the U.S. aid program and the Coalition Support Funds that sustain its battles against the Pakistani Taliban. It may be a bad marriage, once again, but not one that affords an easy divorce. Perhaps a separation, followed by reconciliation?

Both Pakistan and the U.S. should be careful to keep the tone of public rhetoric down and continue the private dialogues that may yet yield agreement on common objectives. Pakistan needs U.S. help to create the stability inside Pakistan that will allow it to fight the immediate war on poverty and underdevelopment. Faced with a rising population and an ever present youth bulge, Pakistan needs to begin to govern itself better, think long term, and eschew factional politics. Its military needs the tools and the time to keep the militancy at bay but it also needs close cooperation with the civilian agencies to help it fight against terrorism in its multifarious forms inside Pakistan.

Osama bin Laden’s death may exacerbate the terrorist conditions inside Pakistan for the short run. Followers and sympathizers of al-Qaeda may well try to seek revenge against U.S. interests and the Pakistani state. But the death of al-Qaeda’s founder should not change the course that Pakistan is following to battle militancy at home and needs to follow in its neighborhood. Nor should the United States pack up and summarily exit the regional stage once more.

Shuja Nawaz is director of the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center. This essay first appeared at Foreign Policy’s AfPak Channel.