The 21st century has ushered in changes in the global political landscape that demand a transformation of the mindset of policymakers around the globe. NATO and the European Union no longer inhabit a world of black and white, with a clear and defined set of antagonists and allies. Global issues that bring together North America and Europe and help create partnerships with other countries around the world too often separate the allies.

Climate change, trade, energy dependence, and access to resources of the international financial institutions – all these issues create different dynamics among nations and groups of nations. Political allies become economic competitors. A U.S.-India civilian nuclear deal may be celebrated one day, but a bitter battle between these two “friends” erupts the next day, when discussions on greenhouse gases takes place in the context of global warming. China and the U.S. become co-dependent in trade but clash on the environment. Similarly, a West dependent on Middle Eastern oil finds itself coping with hostility on political issues such as Israel and the rights of the Palestinians, or the management of the international financial institutions. And some denizens of the Muslim world have sworn lasting enmity against some Western nations. Yes, most of the attackers that took part in the suicide missions against the United States on September 11, 2001 were from the U.S.’s major Middle East ally: Saudi Arabia. Today, the United States is Pakistan’s major trading partner and supplier of economic assistance. Yet, according to an August 2009 poll by the Pew Research Center, some 64 percent of Pakistanis surveyed regard the United States as an enemy of Pakistan.

How does one explain these contradictory trends? How should one attempt to unravel these issues and improve relationships between countries? What are the barriers that remain today, and how can we dismantle them?

A basic problem that affects relationships between the West and the rest of the world has been the focus on government-to-government ties. Somehow, the post-World War II relationships that brought the people of North America and Europe together got lost in the noise and confusion of the 20th century. It became harder for friends of the United States in Europe and other parts of the world to relate to the United States as a congeries of peoples, much like themselves, and devoted to helping others and understanding them. Overarching themes, such as the Cold War, began guiding relationships. Alliances were struck by the West, not with countries but with ruling elites or often single individuals that ruled with an iron fist. This confused the inhabitants of the new nations of the world that were emerging from colonialism. How could the nations that espoused democratic values be blind to the depredations of their allied rulers in the Third World?

Today, similar mistakes continue to be made. In pursuit of a “global war on terror” or to assure access to energy resources, relationships are being fostered with rulers, not with the people of the countries they rule. Those people see a major disconnect between the principles the Western alliance stands for at home and the actions that Western governments appear to be taking abroad. A much sharper focus needs to be put on relations with civil society and economic partners inside the countries that the West wants as friends. Greater social and cultural interaction and a greater ability of the people of the world to travel to the West would help eliminate some of the emerging barriers of distrust. Yet, the emphasis on security seems to be working the other way: bringing down the shutters on social intercourse and especially travel. The default option seems to be: suspect everyone in order to prevent the very few that mean us harm. The result is that we anger and antagonize most of our potential partners in the countries that we need as friends. And we fall back on dealing with the complaint leaders. The disconnect widens. The militants inside developing societies profit from that widening gap.

The West needs to come up with better, less intrusive means of vetting travelers from the developing world so everyone is not treated as a “suspect” and considered “guilty until proven innocent.” Arbitrary detention and deportation do not help create friends for the West either. As Western populations age, their economies will badly need an infusion of labor from these countries. They should begin preparing for that. Even Japan, a bastion of purity in terms of its national population, has opened the doors, though somewhat grudgingly, to other nationalities. Yes, this will change the nature of Western societies as we know them today. But it will also make them stronger and more resilient, and more aware of global pluralism. Along with greater labor mobility across the globe, the West needs to follow its own economic precepts and allow for freer trade, knocking down tariff and non-tariff barriers alike, so the less developed parts of the world can benefit from increased trade opportunities and help themselves. Over time, this would help reduce aid dependency. But this can only be done if civic and political leaders exhibit the vision that will transform them from simple leaders to statesmen.

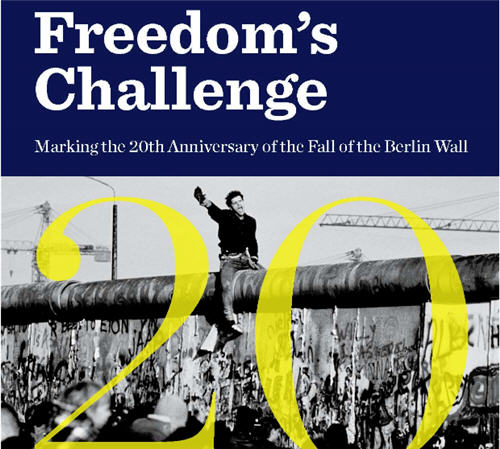

Talking about Islamic militancy also creates a division. The “we” and “they” syndrome fosters the creation of new barriers, much more divisive than the Berlin Wall. Instead of resorting to such broad characterizations of the Muslim world, we must recognize the causes of unrest and militancy, and the West must be seen as aiding and abetting the forces of change and modernity inside those countries, not the anachronistic power structures or autocrats who serve the West’s short-term interests. When the West’s actions begin matching its pronouncements of the principles of freedom and democracy, the barriers will begin to crumble.

Most denizens of the Muslim world seek a voice in their own government. They resent the privileged access to state resources of the connected few. When they stand up to dictators and hereditary rulers who do not respect their own people, the West needs to stand by them, as it did with the people of East Berlin. And it must do so consistently. Only such actions will bring down the emerging barriers across the globe.

Shuja Nawaz is director of the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center. This essay is from Freedom’s Challenge, an Atlantic Council publication commemorating the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall.