THE ATLANTIC COUNCIL

OF THE UNITED STATES

THE INDIAN OCEAN 2020: THE INDIAN VIEW

WELCOME AND MODERATOR:

SHUJA NAWAZ,

DIRECTOR, SOUTH ASIA CENTER,

ATLANTIC COUNCIL

SPEAKER:

ADM. RAJA MENON,

FORMER CAREER OFFICER,

INDIAN MILITARY

FRIDAY, JUNE 25, 2010

WASHINGTON, D.C.

Transcript by

Federal News Service

Washington, D.C.

SHUJA NAWAZ: For those of you that don’t know me, I’m Shuja Nawaz. I’m the director of the South Asia Center. And I’m extremely delighted today to welcome Adm. Raja Menon, who is going to be speaking on “The Indian Ocean 2020: The Indian View.”

And I should clarify that the topic should not mislead you into thinking that this is only going to be about the navy, although if he were to speak only about naval strategy, that would keep us enthralled. But by the Indian Ocean, we really are looking at the littoral states, which has been an interest of India in the 20th century and now in the 21st century because of its rising economic and political power, as well as a need to protect its trade routes.

When I first heard from Raja about this topic, I was reminded of something that was attributed to Haider Ali, the ruler of Mysore. Haider and his son Tipu were constantly trying to reach the coast, because they discovered that the British had a navy and they could move around at will. And I actually have a quote from Haider which I used in my book in which he said, “I can defeat them,” meaning the British, “on land, but I cannot swallow the sea.” So the sea obviously plays an important role in strategy in our part of the world.

And so we’re looking forward to hearing from Adm. Menon on how India views its responsibilities and its role in the Indian Ocean and vis-à-vis the littoral states. And I assume that means everything from the Malacca Straits to the Cape of Good Hope. Of course, India is already participating in anti-pirate operations, and the chances of militant and terrorist attacks coming from the sea have now become a reality after Mumbai. So there are lots of issues that we look forward to.

A little bit of background on Adm. Menon. He is obviously a naval officer, retired in 1994. He is a pioneer of the Indian submarine service, and, in fact, since his retirement, has been very active on the Track II business. He was in the first delegation that went to Pakistan on confidence-building measures. He, after retirement, has been prolific as an author. He authored “Maritime Strategy in Continental Wars,” which is apparently now a standard text in the Indian navy, and “A Nuclear Strategy for India,” which led to his conducting the first nuclear management course for the Indian armed forces officers. And then he was in the group advising the Arun Singh Committee on Higher Defense Management in the National Defense University committee. And he led the group that recently wrote the Indian navy’s maritime strategy and maritime doctrine. Until recently he was the chairman of the Task Force on Net Assessment and Simulation in the National Security Council.

And interestingly, he chose to break away from the constraints of officialdom and has authored a magnificent book called “The Long View from Delhi” to define the Indian grand strategy for foreign policy, which has just been issued in India, and it’s also available through Amazon and other sources in the United States. In this he used the net-assessment approach to basically outline all kinds of scenarios, which I guess the Baboos (sp) were not willing to accept. And so he decided to do it on his own. And I assure you that when you see that book, you will be amazed at the breadth and the depth of his knowledge.

So with that, I’m going to hand over to Adm. Menon. You’ll speak for about 20, 25 minutes, and then we’ll take questions.

ADM. MENON: Thank you, Shuja. Thank you, Admiral.

The reputation of your institution precedes you. I’ve known many people who’ve come here before. It is a great pleasure for me to be given a few minutes to speak at this institution, apart from which I admire Shuja’s book and the many conversations we’ve had on the intricacies of how South Asia is run, or sometimes not run.

At the start of my subject, there are many studies which say that India was always a maritime power, which is strictly not true. That’s more patriotism than logic. We were a maritime power a thousand years ago. And there was an original Indian Ocean trading pattern which can never be restored anymore. That’s because the prime trading partner of every Indian Ocean littoral country is somebody outside the Indian Ocean. So there’s no point in trying to recreate what the Indian Ocean was.

But in the old days, what India was foremost in was the (builders’ ?) counting system, which was the original traditional method of the equivalent of letters of credit. If a cargo of ivory was taken from Tanzania to Saudi Arabia, the risk for that cargo was paid by Indian merchants. And there were these huge trading communities, the Kachis (ph) in the west and the Chettiars in the east, who took the financial risk, which was later on taken over by the Baghdadi Jews. So that’s an old tradition. And no one’s thinking that we can go back to it.

So its maritime heritage really ends when the Europeans came in. Since independence, we’ve had to reinvestigate what the actual facts were about India’s maritime power. And the facts that emerged is something which is not yet in the published domain, which is that the British were seriously concerned with the fact that (peak ?) ships last 150 years, whereas – (inaudible) – ships last only about 40 years. And there was a move, therefore, to kill Indian shipbuilding in the 19th century, so, as a result of which, a law was passed in 1868 which forbade India to have a navy. And the maritime defense of India passed to the commander in chief, Far East Fleet in Singapore.

India would then pay a certain amount of money for the maritime defense, and that money was actually paid by the Indian exchequer to the British exchequer until 1939, when the Second World War broke out. Now, the result of this is that you see the great movements of the British empire, like the establishment of Iraq – such a classic case – Iraq was established by the Indian army in conjunction with the British fleet from Singapore. So the command of the forces that set up the state of Iraq, 1922 – 1918 to 1928 – you find that the military commander was from the Indian army. The political adviser came from Whitehall. And that’s how the British operated.

So whereas India did have an army before 1947, it never had a navy. It was the Royal Indian Marine, whose responsibility now is virtually equal to that of the Coast Guard. So we really had to start from scratch in 1947. Now, the issue is that until 1991, the Indian navy was seriously underfunded, getting something like 12 percent of the defense budget. And during times of crisis, it sometimes fell to 3 or 4 percent of the defense budget.

But since ’91, the Navy’s share of the defense budget has constantly grown at an average of about half a percent a year. So it stands at just short of 18 percent. And this is before the public political acknowledgement that India needs to spend more money on its maritime defense. So I’m making a projection that this 18 percent of what the budget reallocation is now will probably continue to go up to about 21 or 22.

And because of that, there is a feeling that when we look at the budgets of all the other countries, there is an acknowledgement that there are only two navies which are substantially growing in the world today. One is the Indian navy and the other is the Chinese navy. So this leads most people who are involved in maritime thinking to say that we need a vision. We need a vision of what the maritime situation will be. And navies, as you know, take 30 years to build. And we need this vision well in advance if we want to know where we are going, which is the reason why I’ve given the subject, which is the vision of the Indian Ocean, the view from Delhi, 2020.

At the same time, we are more than aware that the supreme maritime power in the Indian Ocean is the United States Navy. That’s why it’s a world power. And you’re a world power because, in any part of the world, you’re the supreme power. Now, this was an area of contention. This was a subject of contention during the Cold War. But with the end of the Cold War, that’s disappeared.

The substance of this contention used to take the form of what I might call shadow boxing, shadow boxing over Diego Garcia. “Why are the Americans in Diego Garcia?” to which the western alliance would say, “Well, what are the Russians doing around in Socotra?”

So there was this continuous shadow boxing and the presence of how many ships from each alliance is in the Indian Ocean. India is at peace with Diego Garcia now. That is, it doesn’t figure in any discussion. But what is more is that we had a visit from CENTCOM about five years, seven years ago, and he put the objectives of the CENTCOM on the slide. And if you took off the heading, it looked virtually like the maritime interests of India. So there is an automatic identity of objectives and views.

Now, you might think this a bit funny, because India is actually in the area of responsibility of PACOM. Now, this has again been the subject of much discussion with the Americans as to the fact that it is CNC Pacific who is charged to look at our area, but our interests seem to coincide with those of CENTCOM. The Americans clearly are not going to change their area of responsibilities of the world to suit our convenience, but this is an outstanding issue as far as we are concerned.

I have to make some assumptions. One, of course, is that, you know, navies are hugely expensive. For instance, the Indian army is 22 times our size, but the amount of money that the Indian army gets for its new equipment is exactly the same as ours, which means to say that armies are much cheaper than navies. But how much cheaper? There is the 70-30, which is that the army spends 30 percent of its budget on equipment and 70 percent on running itself. In the navy, it’s the other way around.

So the reason why I mention this is because, at the political level, the politicians are aware that this service, you know, which leaves its port and then disappears, is performing a duty which they can’t see. And they want to know, what is the return that a navy gives? And it’s very difficult to educate politicians about the intricacies of maritime strategy and positional warfare and issues like that.

So we have to get at what bothers a politician, which is geopolitics. And there is a dysfunction here in the sense that there are a huge number of navies in the Indian Ocean who have no geopolitical problems, (particularly ?) the Europeans. And for them, the primary mission is catching pirates and humanitarian.

Now, this is not an area we can enter into and satisfy the politicians that the money they were allocated, this huge money, is actually being wisely spent. So in our area, in our era of development, we still have to convince the politicians that the problems that we address are primarily geopolitical problems and not those of humanitarianism or catching – law and order, constabulatory, or catching pirates. So this is something that’s got to be understood. So when navies come to the Indian Ocean and say, you know, “Let’s cooperate on catching pirates,” this is good, okay. But we can’t spend too much time on this. Otherwise they’ll send us back to 12 percent.

The other, of course, is I’m mentioning what the facts are for any navy. It’s not anything particular to the Indian navy. The other, of course, is (slot ?) interdiction. Now, this is something which needs to – it’s a complex issue. We need to look at this a bit carefully. When you say interdict it means, you know, you can virtually stop that line of communication. That is hugely expensive, for two reasons.

One is that the naval platforms that interdict could either be operating in an area of their own superiority or in an area of somebody else’s superiority. If you’re operating in an area of somebody else’s superiority, the only platforms that can do this are submarines.

Now, submarines today for most countries mean diesel submarines. If you’re talking about diesel submarines beyond 1,500 miles from your home base, you need three submarines to maintain one on patrol. Most navies have only six submarines.

So, when you talk about the interdiction capability of navies, it’s fairly small. I mean, navies that can actually interdict sea lines of communication are probably U.S. Navy or Australian navy or the Indian navy. That’s it.

If you intend to interdict sea lines of communication in an area of your own superiority, then you have the capability to selectively interdict, and that is absolutely vital because no country carries all its cargo in its own ships, so when you stop a ship at sea, you don’t know whose ship it is.

Let me give you some figures. Let’s take China, for instance. Chinese oil is carried in something like 54 percent in ships which are registered in flags of convenience like Panama, Liberia, places like that. It’s only 46 percent that carry their own. So if you see a Chinese flag, you’ll only see one in two ships. The rest will be in some other.

This may not be the same true for gas carriers, but what we call the problem of flagging means that interdiction requires a huge amount of selectivity. Now, sometimes navies try to get over this by – you know, like channels for immigration.

So, you know, you channel ships through a lane. Now, if you want to do that, you need the backing of, who is a big guy around that place? So, this is an international problem in which the laws are pretty vague but invariably what happens in the end is that might is taken to be right.

Back to geopolitics. There is sometimes a view that conflict can occur at sea. Now, this is a bit far-fetched. My own view is that conflict at sea is invariably a spillover of conflict on land, and there are any number of cases where conflicts can occur on land from which the spillover will come over to the sea, and there are some markers for the possibilities of conflict which we need to look at.

The primary one is demographics. Demographics, they say, is destiny. I mean, this is the one projection from which you cannot escape. People are going to roughly number what the projections say. And if you look at the projections you’ll immediately see what areas of the Indian Ocean cannot escape turbulence and loss of governance.

The primary area – let me put it this way: Demographic turbulence can lead to two outcomes. One of them is that the status becomes ungovernable and therefore spirals out of control. The other is that the state merely declines but is still governed to a certain extent. And these two divisions – there is a division here and some states will fall into one and some states will fall into the other.

The area that is of greatest concern which we need to accept as an international problem is the Horn of Africa. Now, there is no point really in saying that it’s Somalia or it’s Eritrea or it’s Ethiopia or it’s Yemen. The entire Horn is going to spiral out of control. And the reason for this largely demographic – the Horn of Africa and Yemen, by 2050, is going to have the same number of people as the United States. That’s 350 million.

Now, there is already no governance in that area. Somalia is already ungovernable. So, a number of problems flow from that, to say that, you know, we think the problem in Somalia is that it may become a caliphate. Now, you’re merely saying that, you know, this patient has temperature. What you’re not saying is that this patient is ill. So you’re really looking at the symptoms.

Yemen, in our opinion, is going to become ungovernable in another 10 or 15 years. The fertility rate there is five. The government barely functions. It has got no oil. And it’s going to spiral out of control. I mean, you already had one outstanding product – Osama bin Laden.

So, the Horn of Africa is critical as far as geopolitical instability is concerned and maritime effects are concerned because of the waterway in between, which is – (inaudible). So, if you look along the other coast – so what’s going to happen here is that there’s going to be huge migration and it’s going to spin off poverty-stricken people to all parts of the globe, and among them will come mixed fundamentalists, radicalists and so on and so forth.

The problem in Somalia is, again, very strange in the sense that it is ungovernable. It’s got – actually it’s only got about 9 or 11 million people, but, again, they have a fertility rate of five and they’re going to stabilize at, you know, 34 (million) or 45 million in Somalia.

But a lot of social scientists keep pointing out the fact that, you know, Somalis are poor fellows. You know, they don’t catch any fish, and therefore that explains piracy. I find this a bit bizarre. You know, I come from a coastal state myself – you know, Kerala – and all the fishermen go out in the morning and they come back with very few fish, but it doesn’t mean you go out and catch some ships.

So, the fact is that the Somalis have a long tradition of piracy. That Island of Suqutra that lies in the mouth of the Bab el Mendeb has been known for piracy since 1200, since the time of Al-Beruni and even Battuta. So there is a traditional problem there.

As far as unstable regimes are concerned whose unraveling could affect, I think the number-one candidate is those generals in Myanmar. This is something on which we’ve had many discussions with the Americans. That military regime has a limited life.

I mean, you can take a call maybe five years, maybe 10 years, but when the military junta collapses in Myanmar, it’s going to – the minorities are going to spring apart because the agreement between the minorities – the agreement is between the minorities and the Burman army.

So it would be nice to have democracy and Aung San Suu Kyi back as the elected leader, but without the Burman army, the minorities are not going to agree to stay in Myanmar. And the problem is that the minorities next to Thailand, for instance, would much rather be in Thailand.

The minorities in the north, the Shans, have already intermarried with the Chinese, with the Shans in Yunnan. In fact, the Chinese have virtually married their way south as far as Mandalay where you see signs in Mandarin. And all the road signs in Mandalay and shop signs are in Mandarin today. And the idea that the Shans would stay pacified within a democratic Burma is a bit difficult to believe.

So there are issues in the sense that China has, as one of the papers reported, they put lots of money into countries which are described as virtual train wrecks. So they’ve got these five pipelines which go from Sui and they supply the gas in Yunnan. So, what’s the Chinese going to do if the pipeline – which the pipeline will defiantly be affected. So there are those kinds of issues.

In the other area where the maritime spillover of that is concerned is that most of the gas of Myanmar are in the offshore fields. I mean, we were offered gas in the Sui fields and port, but we simply don’t have the money to compete with the Chinese. It would have been a good idea to go and build a port exactly on the other side of the headland where the Chinese are. It’s a very seductive idea. We don’t have the money.

Similarly, we have been offered rights to build access up the Caledon River, up to the northeast of India near Manipur. Again, we don’t have the money. And that was an idea which was floated by us because the Bangladeshis were not being kind to the idea of transit through Bangladesh to the northeast of India, but now the Bangladeshis have come around and have said, you can have access to Chittagong.

So, these developments have got to be watched, and I think these are the maritime outcomes of geopolitical problems. The Afghan war – I mean, there is so much literature about this that I really don’t want to go into this.

The issue is – the war in Afghanistan requires a strong U.S. maritime presence in the north Arabian Sea, you know, partly because it provides the military air cover and partly because almost 80 percent of the heavy stuff still comes in by sea, goes up by convoy from Karachi. So, how long is this going to continue is an issue that needs to be looked at.

I’m told by varying sources that, what’s going to happen to the 1 trillion (dollars) worth of lithium that’s been found? Now, it clearly can’t be left there. Somebody is going to want it. Now, who is that somebody? There are varying views.

I mean, some of my U.S. friends say, yeah, we would like to have some of that because that’s really going to change the future of alternative energy because there’s no energy sink that doesn’t require lithium. If the U.S. doesn’t want it, maybe the Chinese will, or maybe the Indians will compete. Now, Afghanistan is in many ways better approached from the sea, from Iran, Chabahar Port and up the Indian road.

There is the issue of Iran and nuclear – I mean, a lot of people think that the problem of Iran is nuclear proliferation. In a way, yes, but that’s again saying that, you know, this guy’s got fever, not saying why he’s got fever. If Iran proliferates in any way, there is no doubt in our minds – I assume there is no doubt in your minds – that it’s going to have a cascading effect. There will be demands, as there already area, for a Sunni bomb.

And there are people already fishing in troubled waters with Chinese export of ballistic missiles to Saudi Arabia. There are already 14 applications for reactors from the sheikdoms – Egypt and Saudi Arabia – for nuclear reactors to the IAEA. It’s legitimate – Article IV of the NPT – but everyone knows what’s the subtext as to why these nuclear reactors are being asked for.

So, the cascading effect requires that the stabilization of the Middle East, which has traditionally been a maritime issue – you know, people have said that the reason why all these powers are there in the Middle East is because it’s an iron ring around the area of oil, and if the Middle East grew – as a British economist said, if it grew carrots instead of oil, nobody would be interested in the Middle East.

So, the stabilization of the Middle East, the stabilization of the price of oil, oil not running out of control, is going to be largely affected by diplomacy backed by force, and that force will come from the sea.

The last issue of course is that just because a large country is not in the Indian Ocean, it doesn’t mean it’s not actually there. I talk of what is euphemistically called extra-territorial presence, and that’s mainly now. It used to be the United States and Russia; now it’s the United States and possibly China.

Now, we all agree that the greatest political event of the last hundred years is the rise of China, not whether it’s going to rise – it’s already risen, but it’s risen in a way in which other countries have not risen. The pattern that it has chosen to rise in is different from the way other countries have risen in the past.

One of them is that there seems to be, among the geopolitical track in Beijing and the geoeconomic track, at the moment definitely the geoeconomic track is stronger and more powerful because they have to clock 9 percent, as we do. And the strategy they have chosen, and the way we see it, is that they are going to export their way to prosperity, riding on the back of a undervalued yuan.

Now, this has its cascading effect in society on trade and in the world in general. This requires that these export figures need to – the only word I can describe for it, it needs to hurtle along. But what’s happened so far is the attempt to make the Chinese exports hurtle along is that they have created a huge amount of surplus money, which they have found convenient to deposit only in U.S. Treasury bonds.

The sum has now become so big that it is virtually untouchable without destabilizing the international financial system. So there are many economists who put it very boldly and say, the Chinese can virtually kiss their money goodbye, the money that’s in the United States. Any attempt to take away large quantities of it is going to seriously destabilize both the dollar and the yuan and the international system.

But it appears that the Chinese have taken a decision that if you’ve got this problem, you don’t want to make it any worse, so we might not be able to touch our money in Washington but we’re not going to put anymore there, which seems to be the reason why we find, in the last five to 10 years, an incredible amount of Chinese money going into buying assets abroad.

We’ve done calculations and found that the Chinese are in every single littoral state of Africa, from Egypt all the way down, except for four states in the West African – (inaudible). They are all over Africa. And if that’s not enough, now they have started putting money into South America.

Now, this has a number of implications. One is that countries that need resources don’t necessarily have to buy lithium mines. I mean, if you want oil, you go and buy oil. You don’t necessarily have to go and buy it in an oil field. But the Chinese have chosen – they have deliberately made a choice that they are in a financially strong position and therefore they need to buy – they will buy oilfields rather than oil, or lithium mines rather than lithium.

The result of this is that they are going back to a 19th century mercantilist Malthusian geoeconomic strategy when in fact the world is trying to move on with Bretton Woods, that the international system – the international marketing system – you rely on supply and demand.

So, what they are in fact doing but not saying is that they’re going to buy assets and take it out of the market. But do they have any choice? I’m not saying this is good or bad, this is evil or – but this is a strategy they have chosen and this seems to – they feel that this is their best strategy, that if they put money into Angola, they will also build Angola’s infrastructure as payment for the oil rights, but the infrastructure will be built by Chinese labor using Chinese capital equipment, which then increases Chinese exports.

So, it all fits in with this whole pattern, but is this pattern sustainable? There are serious questions – which, as Shuja says, in the book I had an economist holding my hand to answer the difficult ones. If China is to really raise its per capita income from $4,000 or $5,000, where it is today, to 20,000 (dollars), it will have to export nine times the amount what it does. Can the world absorb that much without a lot of countries going bankrupt and not being able to export anything else?

The other issue is that if the Chinese are going to deposit their money, people and capital equipment all over the world, the other departments of the Chinese government are going to move to fulfill their duties, which is the PLA navy and the PLA air force and the PLA foreign service.

And in that movement away from China to South America – and we have seen in the last week they have deposited 20 million (dollars) to build a port in Piraeus, in Greece, which they have been given the rights for for 20 years.

They need to run past us. They need to run past us. And in running past us, if they were to turn around and say, you know, do you mind; excuse me, we have to go – that’s not the attitude they take. The attitude they take is that, you know, lump it or leave it. So, this is going to result in a geopolitical confrontation which is initiated by them, the consequences of which I’m not sure they themselves see the full consequences of it.

So, what’s going to happen is that a number of countries in which a huge amount of Chinese money is invested are going to start – as I said, are going to start bending to the Chinese wind, which means that they will start voting Chinese in the U.N. They will start voting Chinese for the NPT or in the Committee on Disarmament or in Geneva or in human rights. And this is going to inevitably result in a clash with the United States. It’s not our fight, okay, but it will still result in a fight with the United States, which thinks its democracy is worth fighting for.

So, we see that these are issues on which we cannot remain neutral, uncommitted, and we have to take a stand because we are fairly convinced that if we lose our existing superiority in the Indian Ocean, we have nothing left to bargain with. In the last two years we have seen that the Chinese have escalated continuously on our Indo-Tibetan border for no apparent reason, and this seems to be part of the plan to run past us.

So, I think I’ve said enough. I’m sure there are a huge number of issues which I have not covered, but are probably left better for questions. Thank you. Thank you very much.

MR. NAWAZ: Thank you, Raja. I’m sure everyone will agree that my introduction was not exaggerated. There is a naval officer, a military man, who has been thinking strategy and grand strategy for quite a while. And, clearly, the span of this morning’s discussion and talk by him indicates that he doesn’t – he’s not constrained by geography, intellectual or otherwise.

Let me see if I can take you back to a couple of things that you said – one, that the possibility of naval conflict would only arise if there was a land conflict, and yet, near the end of your talk, you were talking about the Chinese shipping lanes or ability to go past India to sources of resources, to natural resources in South America and in Africa – would have to go through India or through India’s ocean, as it were, and that might create a conflict.

So, is there a contradiction here? I mean, are we seeing a naval conflict actually provoking a land conflict?

ADM. MENON: This is a very astute question. What the Chinese are doing is expanding hugely their sea lines of communication through the Indian Ocean, which is a legitimate activity. But at the same time, they are taking measures which – unilaterally taking measures to defend those lines of communication when there is actually no geopolitical threat to those lines of communication.

They are paranoid about the Straits of Malacca. They say it’s a very narrow strait, but so what? Ships pass through narrow straits all the time. But they say, you might block us. But why would someone block you unless you’ve got some nasty thoughts in your mind which you intend to execute some other places, in which case somebody might decide to get tough with you in the Straits of Malacca?

But otherwise, do you accept the international system, which is that, you know, your ships have got to pass through the Panama Canal, they have to pass through the English Channel, they have to pass through the Straits of Malacca? These are inherently difficult rules.

So, just because they’re difficult rules, if you start avoiding them for the sake of geopolitical conflict, the outlines of which no one is clear about – like, for instance they say they want to build a canal through the Kra Isthmus. They want to build a pipeline from Gwadar to take all the oil to Xinjiang. It’s a monumental project and it’s going to cost a huge amount of money. Why do you want to do that? Because I don’t want to go through the Straits of Malacca. So they seem to be jumping the gun.

Now, when you see a movement like that where they’re intending to jump the gun, along with, say, an escalation in the Taiwan Straits or an escalation on the Tibetan border, then you have to conclude that these are all interlinked, but the issue is, who is going to trigger it off?

The only person it would seem who is going to trigger it off is that country which is not accepting the Bretton Woods international flow of marketing system and would therefore go mercantilist and therefore is thinking one step ahead to start defending itself.

So, the issue is that nobody is going to attack China at sea on a clear day out of the blue, but both China and other countries are aware that should something else occur somewhere else, then there is a possibility that the extended lines of communication of the Chinese in the Indian Ocean could come under threat.

It would be a good idea for people to sit across the table and say, let’s decide what’s the first step and what’s the second step. Well, that hasn’t occurred so far. The Chinese don’t talk to us on this issue.

MR. NAWAZ: We have a question from Harlan. Can you use that microphone so we can get the questions also? And if you don’t mind introducing yourselves so we can get it on the transcript.

Q: Admiral, thank you for a – (inaudible, off mike). An observation and a question. I have always been amused that Pakistan’s paranoid insecurity vis-à-vis India is matched by India’s paranoia and insecurity vis-à-vis China. And I would only suggest that in your economic analysis, if you go back and take a look at the four principles that dominate the party’s role of China and indeed the PLA, number one is maintaining stability.

And that defines very, very simply avoiding, over the millennia, peasant rebellion, as the Taiping Rebellion in the 1860s threatened to overthrow that dynasty. And I think today one of the big problems that the Chinese have is that it’s not so much the peasant farmer rebellion but it’s that of the workers.

And, as you know, there are 300 million underclass Chinese, more or less, living under the standard – under the poverty line. And so, I think a lot of things are motivated – and we often underestimate the power of maintaining domestic stability in dealing with this, and China is a great restraint. That’s my observation.

My question really is, given all these things – and I agree with your geostrategic and geoeconomic analysis, the pressure of demographics, radicalism – what concrete suggestions do you have that would engage India possibly more with NATO, the West, regional solutions in Afghanistan?

The U.S. Navy, a number of years ago, proposed the so-called “thousand-ship navy,” which was going to be a voluntary mixture of commercial as well as naval ships exchanging information and so forth. Could you share with us some of your suggestions and recommendations as how countries like – great countries like India might be able to put in place new systems, new institutions, new means for dealing with this instability, which is going to increase?

ADM. MENON: Thank you on your outstanding contributions.

The communist army is traditionally political tools within a country. I totally agree with that. Mao said, “Power grows from the barrel of a gun.” And this is the reason why communist armed forces look like communist armed forces.

I mean, whether you take the East German navy or the Romanian navy or the old North Vietnamese army, they all look alike. It looks like a communist navy, because for the communist countries, navies are a seaward extension of armies, which is the reason why the PLAN is called PLAN. It’s the PLA navy.

And since I spent so many years in Russia, the generic word for the armed forces is armiya. And the glavstav (ph), which is the main staff in Moscow, is heavily army dominated because, as you quite rightly say, it’s the army that will keep the people in check. Navies can’t keep people in check.

And even a man like Adm. Gorshkov – you know, we watched this quite a few years – we watched his humble body language when in the presence of Marshal Grechko. Marshal Grechko was a very powerful man, and in my opinion he was thick as two planks, but Gorshkov had to show humility to him. And today who remembers Grechko? Gorshkov was the father of the navy.

So, that’s the situation in communist countries. So the fact that the armies are meant for suppressing the people, I mean, that’s accepted. But there is a huge transformation of the PLA that’s going on, and the PLA is beginning to look exactly like the United States army. It’s beginning to look exactly like a shock and awe army. In fact, its composition is beginning to look like the U.S. army – heavy tanks, air cavalry, air mobile, heliborne, airborne combined with heliborne operations.

Now, this is not a people-suppressing army, for which I think they might probably begin to use the people’s militia, which is a paramilitary force, of which they have 3 million. This PLA modernization plan, when it is executed, will bring the PLA down to virtually the same size as our army, 1 million. It’s something like 3 million downsizing past 2 million at the moment. It’s going to, I think, come down to 1 million, but it’s going to be a heavy armored, air mobile, air cavalry mobile force.

In a state-to-state conflict, it’s a frightening army. In a civil disturbance, it’s not. It’s really not structured. Probably the people’s militia is probably better structured today. I mean, if you see the use of the people’s militia to maintain law and order during the Olympics, that’s the way to go. I mean, they are being increasingly drilled to army standards and, you know, you can see how they’re being transformed.

The other one is that – I mean, what can we do? I think the first thing we really need to do is compare assessments. I mean, I would like to put my book, “The Long View from Delhi,” on one side and ask, say, NATO or the United States, now put your book on this table. Let’s first agree on what the world is going to look like.

Now, I am saying that the Horn is going to spiral out of control but I might be talking in the wilderness. Does the United States think so and does the United States think that this is an issue on which there is something worth doing? Do the Europeans think so?

The Europeans, we are very confused with them. We are much clearer as to what the French think, but when you compare what the French think with what the EU thinks with what the NATO thinks, we have no idea where we stand.

So, we need to first agree on what the problem is. Do we agree that demographics is the problem in the Horn of Africa? I think we need to get to first base. And once we agree with that, then we can start saying – and a lot of people are now saying, as far as Somalia is concerned, we must attack the problem from the land.

But what does that mean? Does it mean better policing? How do you address the problem? Do you convince the women not to have so many children? What is it that we intend to do? We need to get to the bottom of this, and certainly as far as Yemen.

At the moment, I think there is no strategic consensus on what the problems of the Indian Ocean are. That’s why this book is the view from Delhi. This is also the view from Delhi. I would really be interested to know whether this can be matched with the view from Brussels or the view from Washington. And I think after that, cobbling together a strategy is quite possible.

Q: Can I follow up on that, Shuja?

I should say that your views on shock and awe – (inaudible, off mike) – but let me just say that, unfortunately, even though that Don Rumsfeld was part of our group, I don’t think Don fully understood what we meant.

ADM. MENON: I know.

Q: At least that wasn’t what happened in Iraqi Freedom.

ADM. MENON: I agree.

Q: That was not shock and awe. That was Desert Storm on steroids.

ADM. MENON: Yeah.

Q: What’s interesting is that the view from Europe on defense is very, very similar. If you take a look at the British, the German and the French white papers last year, they all have the same conclusion: Defense is no longer about defense of the realm; it’s the defense of the individual.

ADM. MENON: Right.

Q: And so your argument, in essence, only gets to their argument because of what the reverberations will be.

I don’t know if you’ve seen the – what the ACT product, the joint future environment? Allied Command Transformation in Europe – Allied Command Transformation in Norfolk did a study last year for NATO on what the future environment was going to look like. It was a fairly superficial study because NATO wasn’t that interested –

ADM. MENON: Right.

Q: – but you may want to take a look at that.

ADM. MENON: Right.

Q: Because I think that your idea is really important, and what one could say is there needs to be the security equivalent of Davos.

ADM. MENON: Right.

Q: And maybe you could start arguing for that – Delhi, NATO, the major powers – to put together a forum whereby people look at what the potential dangers, threats, uncertainties are, develop some kind of baseline, and then from there you could work on the particular strategies and institutions. That’s lacking.

And so, I could not agree more with your approach. The question is you need to find out a way to put that into operation and make it work.

ADM. MENON: Yeah.

Q: Thank you very much, Admiral. My name is Damien Tomkins. I’m from the East-West Center. One quick observation, I think. I think I’m correct when I say that European militaries are reducing – European countries are reducing their defense spending, whereas in Asia, defense spending is on the increase. I kind of have two questions. One is relating to U.S.-India relations and the other one is pertaining to India-China relations.

I don’t know if you have any comments on the recent strategic dialog, anything that came out of that between the United States and India. I was interested – I think Secretary Clinton said at the beginning that the United States carries out more military exercises with India than any other country. I think that that was one of her comments. I don’t know if you could expand on that slightly. And of course, you know, India – we’ve heard of the humanitarian assistance after the tsunami in conjunction with Australia and Japan, the Indian navy, the American Navy working there.

And the other one is a little bit towards China-India relations. Obviously there’s the “string of pearls.” There’s the ports I understand that China is building in Sri Lanka. Of course Qatar – and an airfield possibly in Qatar and Pakistan and Burma. Any thoughts on the “string of pearls”?

And then a little bit different but the India-China border dispute, where is that going? My understanding is that that dispute will not be resolved until the issue of Tibet is resolved, and in China’s – what China wants and also leading into some of the succession regarding the Dalai Lama, and that’s also feeding into that. So, I would be interested in your thoughts. Thanks very much.

ADM. MENON: These strategic talks with the U.S., the – New Delhi is dominated by the economists, and quite rightly. There is no question that the whole country is behind a unified view that what India needs, to the exclusion of practically everything else, is to clock 9 percent for 15 years. And is there a factor that can actually make it clock 9 percent? And is there a factor that can definitely prevent it from clocking 9 percent?

It so happens that that factor is the same thing, which is the youth bulge. We’re going to have 12 million people coming into the workforce between now and 2025. That is the youth dividend. If those 12 million people –

Q: (Inaudible, off mike) – every year?

ADM. MENON: Every year. There’s going to end up something like 300 million. If those 12 million are even just employed, they will generate, on their own, about 2 percent of the GDP – 2 or 3 percent of the GDP. So, it is not a problem clocking 9 percent. If they are unemployed, they are going to detract 2 percent from the GDP, so then it becomes a youth bulge and not a youth dividend.

So, the problem is that the Indian educational institutions today, the infrastructure is not capable of creating skills for 12 million a year. And, quite rightly, the ministers that came here for the strategic talks have focused on this one issue. I have no quarrel with that.

I still doubt the capability of the ministers who came here to actually do something about this because the minister who came here is the minister for education, for the central government, where education is state subject.

And in your case, education is mostly a county subject, so I haven’t understood what these guys came here and talked about. There are counties in the U.S. where the schools are the best in the country, and there are some counties where the schools are the worst. It’s a varying standard. It’s a county decision.

So, in creating skills – let me give you some figures. Imphorsis (ph) and three or four companies have produced five times the number of equivalent engineering graduates as has the education system of the country.

So what’s really happening in India and to the private sector is taking a bunch of unskilled guys and training them to do jobs for them which they would normally acquire – hire graduates for. So they are the equivalent. After 10 years it wouldn’t make a difference if they don’t have a degree but they would have a – (inaudible).

So, the minister coming here creates apprehensions in my mind in the sense that, you know, it would have made much more sense if he had brought Imphorsis’s chairman here or Azim Premji here because these are the guys who are going to turn out more graduates than the minister of education. So I’m a little apprehensive about that but they are looking at the right problem.

But still, the fact that you’re trying to solve the main issue for India doesn’t mean that the country needs to punch below its weight in everything else because it’s got a huge bureaucracy. So the education bureaucracy is getting more on education. It doesn’t mean that the other bureaucracies, you know, are just sitting around.

So, there is no reason why the U.S.-India strategic relationship, the real strategic relationship can’t also be activated. And one of the issues here is the CENTCOM/PACOM business. You know, we don’t know who we should be talking to. PACOM, in my opinion, is transfixed over the Taiwan Strait crisis, and like the Chinese, who are panicking about the Malacca Straits, I frankly don’t think PACOM’s interest goes much beyond the Malacca Straits, and CENTCOM is not entitled to think about it.

So, I mean, we keep feeling that – is there a view in the United States that actually they’re powerful enough to go it alone? We have that suspicion because – they certainly can’t go it along on land but warfare at sea is something else, and it is possible for the United States to go it alone until it gets to problems where, you know, there is a long deployment of ships or anti-piracy where you just need so many ships just hanging around or so many years and then the United States would like to have the assistance of somebody else. But, I mean, they’re not only interested in low-end jobs, you know?

So, this is something that has got to be sorted out at the strategic level, and that has not yet been sorted out. It’s true that we have the largest number of exercises, but this leads to a joint operations capability to do something. What is that something? This is what we keep asking the United States about.

As far as the Sino-Indian thing is concerned, there is nothing that they have done so far that really threatens our security, but they are on the way and we see that we’re leading to results which are not nice.

The Sri Lankans will never allow the Chinese into Hambantota. We are certain about that. And we feel that even the Pakistanis will think twice before they allowed the Chinese Navy into Gwadar for longer than one visit or two visits. But if they intend to maintain a sensible presence, it’s going to require something more than building a harbor in the Indian Ocean.

Now, everyone knows what that is but the Chinese haven’t moved towards that yet. But the fact that they might be able to convert that huge economic presence all over the coast of Africa and other places into something more dual use is – we think it’s a matter of time, and so do the Americans. So, we are watching it. And, as I said, you are right that – you’re also right that there is no need to panic about the Chinese today; it’s tomorrow that we’re worrying about, 2020.

Q: What about the border dispute?

ADM. MENON: Oh, yeah, border dispute. The border dispute is – you know, the thing that really worries us is, to put in a nutshell, the Dalai Lama is almost 80 years old. Now, he’s not going to last forever.

And we get the feeling that they are certainly jerking us around on the border. They are intruding into areas which are ours, leaving telltale signs that they’ve been there and then withdrawing. They are threatening the locals about building roads, saying, you know, you must ask the permission of the Chinese. That’s why our patrols are not there.

So, you know, they are doing all this kind of thing but the issue is this: You know, these incidents are being done by officers of the rank of, say, a captain or a lieutenant. Now, there is no way that an officer of that rank can think up a sophisticated scheme to create an incident unless he has been directly controlled from Beijing because there is no way that a local commander will be told, okay, go and create incidents with the Indians, because nobody in Beijing knows whether that fellow might push things out of control, which is the last thing Beijing wants, but yet they’re creating incidents.

So, in the military we are familiar with this situation where you are actually creating very small incidents but it’s at a geopolitical level because when that captain comes across with 20 men, across the border, it’s a geopolitical incident, and he’s being very tightly controlled. You know it. So it’s the intention behind all of this.

There is also the whole issue of the religiosity. If the Dalai Lama dies, which he will at some time, what’s going to happen next? And whatever the Chinese say – you know, they’ll put up a Dalai Lama and the Tibetans will say, get lost. I mean, this is not the Dalai Lama. So then what are the Chinese going to say? The Tibetans will say – and the Tibetans are all in India and we’re not going to kick them out. That’s what the Chinese want. They want us to hand over these Tibetans back to China, which we won’t.

So, these Tibetans who are in India, who are now a prosperous, thriving community, are going to come up with who they think is their Dalai Lama, and he will be in India. And the Chinese will say, you’re, you know, creating a new Dalai Lama and a problem for us. So we realize all this, but –

Q: So do the Chinese.

ADM. MENON: Yeah, so do the Chinese but, I mean, we’re not going to move from this. I mean, the Tibetans are virtually Indian citizens. They’ve been here for 35 years and a few of them are getting aggressive, no question. But we really restrict – and I feel ashamed – we really restrict the Dalai Lama’s movements to please the Chinese. And I think that’s about as far as we are prepared to go.

MR. NAWAZ: Holly (ph)?

Q: Yes, I have wanted to first make a comment and then raise a question. The comment relates directly to the scenario that you’ve drawn where Chinese capabilities and the increasing ubiquity of Chinese military assets, alongside the mercantilist expansion of Chinese economic interests, leads to a more aggressive Chinese presence globally.

And the comment is, from my discussions over a number of years with Chinese government and non-government scholars, it seems to me that if they were sitting here, somebody would put up a finger and say, well, wouldn’t that lead to Paul Kennedy-esque overextension of the sort that we’ve been laughing at your for?

So I have to raise this question because of course in private discussions these folks say, well, it’s nice of you to secure Afghanistan for us so we could mine minerals, and it does seem to me that they would risk perhaps the same outcome and there might be at least some cautionary lessons to be drawn from our path and our current trajectory.

What I really wanted to ask you about, though, is to think about an end state for arrangements concerning the Indian Ocean that would be satisfying and reassuring to India as we think out 10 or 15 years, and particularly end states that would include some sort of disincentives for China to behave in ways unacceptable to India in the littoral states but even more on the waters that would not disquiet – that would reassure and disquiet the Chinese, not in fact cause them to react neuralgically (ph) but that might neutralize or at least discourage some of the behaviors that you have raised.

So if you think about end states, what would that look like? What are some options for end states that would be reassuring to India without causing new problems? And what are some of the paths for getting to that – you know, multilateral paths, the India-U.S. possibility you have implicitly raised.

And I haven’t had a chance yet because I haven’t gotten my copy, to read your scenarios-based futures book, “The Long View” book. India, U.S, Australia, Japan – what sorts of arrangements, either flexible or more permanent, what sorts of treaties, what kinds of rules of the road might help prevent the outcome that you’re concerned about?

ADM. MENON: Yeah, those are great questions. I agree that the Chinese are very aware of the blunders created by Cecil Rhodes and the colonialist paths taken by Britain and the Western paths. And there are public statements to indicate that they don’t want to go down the same road. But I am less than convinced that they have the intellectual depth to actually create an alternative route. Wanting a route different from colonialism and neocolonialism is one thing, but coming up with an alternative is something quite different.

Now, the route that the Chinese are taking is this: They’re going to the – let’s take Congo. They’re going to the Republic of Congo and they sign a deal with huge corruption with the heads of state. And it is impossible to believe that that huge amount of money that they’ve paid in corruption has not led them to get an agreement which is disadvantageous to the people of the Congo. It’s impossible to believe that.

The structure of the agreement is this: that they will build infrastructure – they’re going to build, I think, two airports, a port, 420 kilometers of highways in return for total mining rights of, I don’t know, 10 years, 15 years for cobalt, lithium, manganese and nickel, things like that.

Now, everyone is very aware that there is no expertise in the Republic of Congo to be able to sign a good agreement. I mean, this is the kind of agreement that if you match the building of infrastructure costing so much, so much, so much, which actually will be built by Chinese labor using Chinese equipment using Chinese money, how do you balance that with 15 years mining rights when in fact you don’t know how much minerals actually are in the ground?

You might end up at a loss. You might end up completely ripping off the Republic of Congo. Everyone knows this. Now, the point is that the Chinese say, well, if you think that we are going to rip off the Republic of Congo, well, why didn’t somebody else come in and make this deal?

The fact is that those who – the other countries will say, okay, we’ll depend upon what the market gives. If the price of lithium goes up and chrome goes up, the people who are involved in that will go and establish new mines.

So, the Chinese – you’re right, you know, they shouldn’t be doing this because they’ll get overextended because once they go there – and all these institutions are being pushed by the Chinese development – Chinese Overseas Bank. It’s a bank that’s doing it, apparently; that’s what the Chinese say, but we don’t know what the connection is between the bank and the state.

And once the bank has done this – like, for instance, let’s say they went into Algeria to take oil and gas, and that’s an area where the kind of incident will occur which we feel will occur because the Chinese go there; they don’t eat anything other than Chinese food. They live in a ghetto. They don’t mix with the local people. They don’t hire local accommodation. And they live in a different way; they live in a more prosperous way than the local, and there have already been riots and Chinese people have been killed, as a result of which I’m sure the Chinese ambassador in Algeria has had to intervene and report back to Beijing.

Now, that will certainly set off, say, the PLA to say, now, what are we doing? These poor Chinese people are going across and creating assets and taking things and they’re bringing it back there, and they’re vulnerable and we need to protect them – normal state activity. So, eventually you will end up in a spiral set of circumstances which will take you down the same road as Cecil Rhodes, as the old colonialism. How will it be any different?

So, if the Chinese think that they are going to create a different route, I would like to hear what this route is. The very basis of the agreements that the Chinese are signing with these African nations is deeply suspect. In fact, Transparency International has volunteered to go and relook at all these agreements to take the agreements on behalf of the African governments to see whether they’ve been given a good deal by the Chinese.

But the guy who signed it for the African government, he’s on the take, so he’s not going to allow that agreement to be re-looked at. And it seems not very far different from the way, you know, the diamond mines were taken over in Botswana in 1818, 1819. So that’s one.

The other is what is the end state in the Indian Ocean and how can we discourage Chinese behavior? My personal view is that the Chinese respect force. They deeply respect force and they don’t – when they are confronted with force, they don’t look at whether the use of that force is meritorious – whether it’s good or whether it’s evil. They are very pragmatic to say, there is force; we have to live with this force.

And let’s take, say, nuclear weapons. I mean, for years we asked the Chinese, let’s talk about nuclear weapons, and they said, you’re a non-nuclear power; there’s nothing to talk. Sign the NPT, give up nuclear weapons and we’ll talk. Eventually, when we went overtly nuclear, they said, okay, let’s talk.

So they’re very pragmatic about it. They say, you know, India has become a nuclear weapon power. There’s no point in pretending they’re not a nuclear weapons power, so in which case let’s talk. But then initially the talks would be very superfluous. They’ll still say, you know, but why don’t you think about going back and not making nuclear weapons? But the talk occurs.

I mean, I was stunned about the report that the Israelis were given a very detailed hearing by the Chinese on what they will do to take apart Iran’s nuclear weapons, and the reason why apparently the Chinese gave them a very good hearing is not because they thought that the Israelis might succeed in taking out their nuclear weapons, but the Israelis told them, we just want you to think what the price of oil will be after our attack. It will be not less than $150. That got the Chinese’s attention.

So, in principle, I think to keep the Chinese toeing the line, a strong force, Indian navy, in the Indian Ocean is a primary requisite – is a primary requisite. And this is taking off from the question asked earlier. And this is an issue on which we have spoken to the Americans and we’ve said, listen, exercising with us is one thing but, I mean, let’s look at our force structure. Everything is Russian. If we have a great strategical relationship with you, why is it that the only ship that we’ve bought from you is 45 years old, the Trenton?

And why is it that, you know, the FMS lists that we get have only got 45-year-old ships when the FMS lists that you show, say, Taiwan – we can understand, okay, Taiwan needs better stuff, the U.K. needs better stuff; they are closer allies, but surely you can do better than this.

So this is an issue on which we need to talk. I mean, a lot of the Americans say, yeah, yeah, we would like to see more of your inventory include American stuff rather than Russian stuff. We don’t mind. That’s something we really need to look at. And, in fact, a lot of ideas have been put into the Pentagon and the State Department. Let’s see where it goes.

The U.S., Japan, Australia, this is classic geopolitics; I agree. I mean, if the two great democracies of Asia, Japan and India – I mean, look where they are. They are 4,000 miles apart. What do they intend doing? I mean, we’ve raised this question with the Japanese and the Japanese get very excited, but I think they are completely suppressed by their civilian bureaucracy.

Even the president of their national defense university is a civil servant. You know, I can’t respect a military like that. I mean, how can you respect a military where the joint services college is headed by a bureaucrat who has never known anything about defense?

So, there is a problem in discussing things with the Japanese. The Australians were fairly gung ho, actually, until about three or four years ago when they signed these huge coal and iron ore deals. And to some extent they give the impression of having rolled over it. They’ve already made statements that the Chinese interest in Taiwan is not in Australia’s interest to contest, or something like that – words to that effect.

Maybe the change in the Australian government will change their stand but this classic geopolitics of linking up the sea space between India and Japan, as you quite rightly say, with using other powers like Singapore and Australia, this is classic geopolitics but so far things – I understand one thing, which is that people might look at the Indian navy and say, now, why do we want to tie up with these guys? They haven’t got enough force. And if we need someone to hold our hand, let’s chose someone who really carries a big stick.

And the Indian sticks aren’t big enough. I understand that. That’s what the Southeast Asians say. They are frightened of China but we don’t give them enough comfort. We need to be more powerful to give the Southeast Asians more comfort. So that’s where it stands then.

MR. NAWAZ: The last question from – (inaudible, off mike).

Q: Stanley Kober with the Cato Institute. You did touch on Afghanistan so I will pursue that.

A lot of news from Afghanistan this week but one story I think has been somewhat obscured. The Polish government has said it wants out, okay? The Dutch, the Canadians have already said they want their troops out. Now Poland says it wants to raise NATO, and even if NATO does not agree, it will pull its troops out, so you can see the mission unraveling.

Just before the McChrystal story broke, there was a front-page story in The Washington Times that I found extraordinary about war weariness in the United States, and Dan (ph) had mentioned in terms of Europe, but also where will the resources come from? This problem is on your doorstep, so if we can’t rely on NATO, what can you do, you know, and what are you looking for in the event down the road in terms of Afghanistan?

MR. : Without making the situation worse.

ADM. MENON: Worse.

Q: Worse, yeah.

ADM. MENON: Quite right. Absolutely right. You know, this is a very contentious issue, and when things get really contentious, the best thing is to game it. We’ve already gamed it and the solution came out, in my opinion, very stark and clear.

As Harlan says, whatever we do mustn’t make it worse, and making it worse means offending Pakistan. Pakistan’s problem is that – I think the best thinkers in Pakistan have already conceded that Afghanistan is not required for strategic depth, that nuclear weapons are their strategic depth. That’s one of the best ideas I’ve heard coming from Pakistan and that makes complete sense. And the idea that people in Islamabad will retreat into Kabul is a daft idea in my opinion in the first place.

But what they don’t want is they don’t want the Indians in Afghanistan in a big way. That is what would worsen the situation. The solution that was suggested was that we should move 30,000 Afghans to India every six months, train them, get senior NCOs back from Afghanistan, their officers, form them into cohesive fighting units – cohesive fighting units, not just turn out a thousand guys in uniform who can fire a gun. That never made any sense to me in the beginning itself.

We have to turn them into a unit that stands, fights and dies together. Somebody’s got to do this, and that’s the best thing that the Indians can do. That shouldn’t worry the Pakistanis because they’re not in Afghanistan. The issue is that – you know, it’s like a game of whispers. When an idea like this is put into the government, it goes from whisper to whisper to whisper, and eventually what comes out is complete nonsense.

So, what’s come out is that the Indians who trained the Afghan army, that wasn’t what we said at all. We said we should train 30,000 every six months, although you can’t affect a central gravity. And so what’s happening is that we are running NCOs’ courses, we are running paratroopers’ courses, we are running junior leaders’ courses, EME courses and engineers’ courses.

And you can maintain an army with this kind of training but you can’t create an army with this kind of training. The inputs have got to be much larger. And I’m not very clear where the dumbness is coming from – from our side or your side. Is it because the Americans are saying, this is not a workable idea? Or is it the Americans have asked this and we have said that this is not a workable idea? I’m not clear, but this very thing was mentioned in the last few days and I said, you know, the only man who can swing something like this is Gen. Petraeus himself, possibly.

From our side, I accept that our army headquarters has stopped thinking geopolitically for some time because it’s been so caught up in counterinsurgency and its hubris in having managed really difficult counterinsurgency problems that is has probably not given enough time to looking at, say, the geopolitical problem in Afghanistan. As you quite rightly say, it’s something that brings the problem to our doorstep.

So, suggestions are there, good suggestions are there, and have probably built this road from Chabahar to Afghanistan. We can lift 30,000 guys every six months, no problem. There are 18 regimental centers and the Indian regimental centers are hundreds and hundreds of acres. This is the army that expanded to 3 million in the Second World War. The same regimental centers are still there, as Pakistan has. They can take on 30,000 without even sneezing. But somebody must make it move, so that’s the issue.

MR. NAWAZ: We have reached 11:30 and that’s the promised hour. I think you’ll all agree with me that Adm. Menon has given us a very rich diet of ideas, and I’m sure that those of you that are interested in following up on that will be immediately be rushing to your computers and ordering the book because even when he is talking about the book and the scenarios, he doesn’t really give away all the information. He wants us to – (laughter) – make sure that we actually read the details. Otherwise it will be the game of whispers again and we may end up completely misconstruing what he was saying.

But I want to thank Adm. Menon on behalf of my colleagues at the Atlantic Council, and also want to thank Alex (sp) and Anna (sp) for having set everything up, and Shikha for having chased him down even when he and I were trying to resolve nuclear issues in Copenhagen between India and Pakistan last weekend, which was an extremely productive meeting, and at some point I think we will be going public with some of our documents.

So, maybe we will entice him to come back and help explain all of that. If not, then have Peter Jones from the University of Ottawa come and join us, which we’ve offered to do at the South Asia Center.

So, with that, I really would like to thank Raja for this talk, and thank all of you for coming and participating in this.

MR. NAWAZ: Here, here.

ADM. MENON: Thank you very much. (Applause.)

The Afghanistan war may be lost on the battlefields of Pakistan, where a vicious conflict is now being fought by Pakistan against a homegrown insurgency spawned by the war across its Western frontier. A year after we at the Atlantic Council raised a warning flag about the effects of failure in Afghanistan and the need to meet Pakistan’s urgent needs in its existential war against militancy and terrorism, the situation in Pakistan remains on edge. Domestic politics remain in a constant state of flux, with some progress toward a democratic polity overshadowed by periodic upheavals and conflicts between the ruling coalition and the emerging judiciary. The military’s actions against the Taliban insurgency appear to have succeeded in dislocating the homegrown terrorists but the necessary civilian effort to complement military action is still not evident. The government does not appear to have the will or the ability to muster support for longer-term reform or sustainable policies. The economy appears to have stabilized somewhat; but security, governance, and energy shortages are major challenges that require strong, consistent, incorruptible leadership rather than political brinkmanship, cronyism, and corruption that remains endemic nationwide. Recent constitutional developments offer a glimmer of hope that may allow the civilian government to restore confidence in its ability to deliver both on the domestic and external front. But the government needs to stop relying on external actors to bail it out and take matters into its own hands.

The Afghanistan war may be lost on the battlefields of Pakistan, where a vicious conflict is now being fought by Pakistan against a homegrown insurgency spawned by the war across its Western frontier. A year after we at the Atlantic Council raised a warning flag about the effects of failure in Afghanistan and the need to meet Pakistan’s urgent needs in its existential war against militancy and terrorism, the situation in Pakistan remains on edge. Domestic politics remain in a constant state of flux, with some progress toward a democratic polity overshadowed by periodic upheavals and conflicts between the ruling coalition and the emerging judiciary. The military’s actions against the Taliban insurgency appear to have succeeded in dislocating the homegrown terrorists but the necessary civilian effort to complement military action is still not evident. The government does not appear to have the will or the ability to muster support for longer-term reform or sustainable policies. The economy appears to have stabilized somewhat; but security, governance, and energy shortages are major challenges that require strong, consistent, incorruptible leadership rather than political brinkmanship, cronyism, and corruption that remains endemic nationwide. Recent constitutional developments offer a glimmer of hope that may allow the civilian government to restore confidence in its ability to deliver both on the domestic and external front. But the government needs to stop relying on external actors to bail it out and take matters into its own hands.

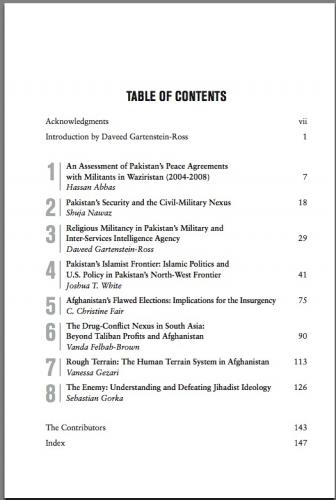

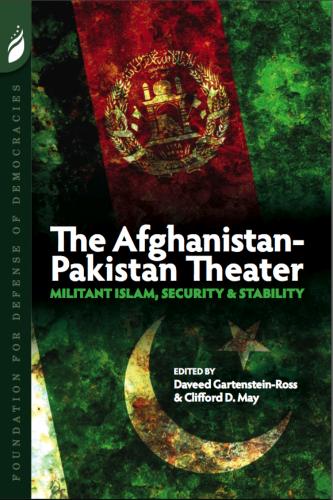

The Afghanistan-Pakistan Theater: Militant Islam, Security and Stability, published by the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, explores vital aspects of the situation the U.S. confronts in both Afghanistan and Pakistan. This collection represents a diversity of political perspectives and policy prescriptions. While nobody believes that the way forward will be easy, there is a pressing need for clear thinking and informed decisions. Contributors include Hassan Abbas, C. Christine Fair, Vanda Felbab-Brown, Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, Vanessa Gezari, Sebastian Gorka, Shuja Nawaz, and Joshua T. White.

The Afghanistan-Pakistan Theater: Militant Islam, Security and Stability, published by the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, explores vital aspects of the situation the U.S. confronts in both Afghanistan and Pakistan. This collection represents a diversity of political perspectives and policy prescriptions. While nobody believes that the way forward will be easy, there is a pressing need for clear thinking and informed decisions. Contributors include Hassan Abbas, C. Christine Fair, Vanda Felbab-Brown, Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, Vanessa Gezari, Sebastian Gorka, Shuja Nawaz, and Joshua T. White.