U.S. President Barack Obama’s announcement yesterday about Osama bin Laden’s death in Abbottabad, Pakistan raises questions about the health of the U.S.-Pakistani relationship. Pakistan seems to have helped the United States track down bin Laden’s lair, as Obama acknowledged. But it is unclear whether Pakistan was involved in planning the mission that brought U.S. Special Forces on helicopters from Afghanistan to deep within Pakistani territory to kill him. If it was not, the raid was yet one more example of the deep distrust between the United States and Pakistan and may reflect poorly on Pakistan’s ability to defend its air space against such intrusions — something that would surely hurt its standing in the eyes of the Pakistani public.

In the United States, Obama’s announcement has been met with a flood of questions about the location of bin Laden’s hideout — it was near a military academy and an army cantonment — and what it means about the Pakistani military’s relationship with bin Laden. Proximity, of course, does not establish a direct association. But if evidence does surface that Pakistani authorizes were complicit in creating the hideout, then all bets are off. The U.S.-Pakistani friendship is in serious trouble.

Of course, the U.S.-Pakistani relationship had seemed to be spiraling downward for some time. On March 17, Pakistan’s army chief, General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, condemned an early March U.S. drone attack in the town of Datta Khel, in the North Waziristan tribal region, that is reported to have killed 41. In his public remarks, Kayani said that “such aggression against [the] people of Pakistan is unjustified and intolerable under any circumstances.” Privately, he warned U.S. interlocutors not to force him "to react" again, hinting at the possibility that Pakistan might start shooting down drones in its territory. At the same time, he announced that he would cut whole categories of U.S. personnel posted in Pakistan, although he did not say which ones.

Then, in mid-April, Lieutenant General Ahmed Shuja Pasha, the head of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence, visited CIA Director Leon Panetta, reportedly to discuss the ISI’s demands for more control over U.S. spy programs in Pakistan. It remains unclear if he pushed for a written agreement on reining in U.S. activities or one on intelligence cooperation, since neither outcome was announced.

The rift comes at a bad time for both countries. The United States needs Pakistani help to stabilize Afghanistan before its planned exit scheduled to begin this July. Moreover, without Pakistani cooperation, it will be impossible to dismantle the Taliban’s safe havens in northwestern Pakistan, or continue to use the land routes over the Afghan-Pakistani border to supply U.S. troops fighting in Afghanistan.

Pakistan also needs the United States — mostly for financial support. The Coalition Support Fund, which the United States set up after 9/11 to reimburse allied countries for their assistance in the war on terror, still covers a large proportion of Pakistan’s military expenditures for counterinsurgency efforts — some $9 billion since the fund was established. Since 2001, the United States has also paid Pakistan $13 billion in military aid and $6.6 billion in economic assistance, with more to come.

Still, the Pakistani military is galled by the general sense that it has been reduced to an army for hire, and many of the generals now argue that the United States is treating the country as a client state, not as an ally. As Kayani’s remarks indicated, the CIA drone strikes in Pakistani territory deeply anger both the Pakistani military and public. It is unclear, however, whether Pakistan will actually refuse to cooperate with the United States, or even could if it wanted to. Behind Kayani’s and Pasha’s tough talk, there is no real consensus between the civilian government and the military on how Pakistan should deal with the United States.

For years, Pakistan’s civilian government, led by President Asif Ali Zardari and Prime Minister Yousaf Raza Gilani, has stoked popular resentment against the drone program by ritualistically denouncing it as an infringement on national sovereignty. (Pakistan’s previous government, that of President Pervez Musharraf, also followed that strategy.) In November 2010, however, WikiLeaks revealed that the Zardari administration had been providing intelligence to the CIA for the program all the while. Now, the civilian government is in an awkward position: it wants the drone attacks to continue on the Pakistani Taliban, which it considers a threat to its rule, but it cannot be caught supporting them again. The Pakistani role in bin Laden’s capture and death will only add to public sentiment against the government.

The civilian government also wants to improve its overall relationship with the United States. Zardari and Gilani’s standing in Pakistan is precarious, and they see the Obama administration as a key pillar of support for their continued rule, even though the United States has often gone directly to the Pakistani military when it wanted something done quickly. Still, in a March 2011 quest to resume the U.S.-Pakistan Strategic Dialogue, which the Zardari administration hoped to use as a venue for bringing together the Pakistani military and civilian government with the U.S. government to improve economic, political, and military ties, Zardari sent his foreign secretary to Washington. And now, Zardari is preparing for his own friendly visit to Washington later this spring.

But already, the civilian government’s plans for reconciliation have started to fall apart. The Strategic Dialogue is lagging; its spring 2011 meeting was postponed indefinitely after the last drone attacks. And the new U.S. special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, Marc Grossman, has yet to take on the task of repairing U.S.-Pakistan ties, having just been named to the post in February. There are indications that his remit will be narrower than that of his predecessor, Richard Holbrooke, and mainly include the economic dialogue Holbrooke initiated.

Moreover, the military’s démarche around the recent Kerry-Lugar bill looms large in the civilian government’s memory. The 2009 bill proposed tripling U.S. aid to the civilian government and placing military aid under some restrictions. The Pakistani military publicly denounced the bill and demanded that the government do the same. The United States then softened the terms of the bill. This was a tremendous embarrassment for Pakistan’s civilian government. But the bill proceeded on course. And by all accounts, it seems to have learned the lesson well, allowing the military to do mostly as it pleases; when questioned after Pasha’s recent trip to Washington, Gilani explained that he had authorized it but could not affirm that he had planned it.

For their part, Pakistan’s military and intelligence are united in their desire to assert their autonomy from the United States. They maintain that, because of its strategic location and importance, Pakistan should have more leeway to drive counterinsurgency operations than it currently does. U.S. funding has been important but many Pakistanis argue that the country gets by mostly thanks to the $10 billion in remittances that come annually from Pakistanis overseas — a much larger financial flow than U.S. aid.

Pakistanis’ growing sense of autarky has led them to overplay their hand in negotiations with the United States. Realistically, the Pakistani economy would collapse without U.S. funding and the accompanying flows from Western international financial agencies, and the military would have to scale back significantly. The military, therefore, would be loath to see U.S. support go but probably does not believe that the United States would cut aid. In fact, although the Kerry-Lugar bill pledges $1.5 billion a year for five years to Pakistan, the United States has not fully committed the funds. This qualification seems to be lost on Pakistanis. When it comes time later this year to plan to release the money for 2012, a cash-strapped U.S. Congress could very well decide that it has better things to pay for than an intransigent Pakistani military.

Indeed, the United States tends to see the greater application of military and political pressure as the key to forcing Pakistan to act, for example, against the Taliban sanctuaries in its territory. This is a mistake. Pressuring Pakistan’s civilian government does not work, because the government is not in a position to guide policy. Applying pressure on the military does not work either, because it only deepens the military’s resistance and does not change its calculation that regional interests are better served by alighnign with insurgents as a hedge against India’s growing role in Afghanistan.

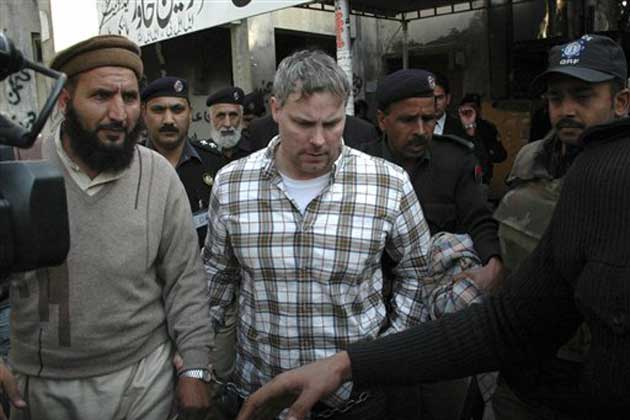

Rather than publicly placing demands on Pakistan, Washington should be working with Pakistan to make counterinsurgency efforts truly cooperative. Although the CIA operates in Pakistan, it appears to share very little information with either the military or civilian government. As controversy over Raymond Davis, a CIA contractor who shot two Pakistanis in the street in Lahore, showed, even U.S. diplomats were barely aware of what CIA agents were doing in the country. In such an atmosphere of mistrust, miscalculation rules on both sides. And although the two militaries seem to work fairly well together on training and joint exercises, their broader relationship would improve if the United States allowed the Pakistani military some participation in strategic decisionmaking, especially in decisions related to the drone program. This is highly unlikely, of course, but important nonetheless.

The alternative is an ever greater U.S.-Pakistani rift. Pakistan’s economy and polity are already in shambles. Sectarian and ethnic violence are increasing. Inflation and shortages of power and food are widespread. Unemployment is rising, and a coming youth bulge portends difficult days ahead. Besides hindering any progress on Afghanistan and insurgency, a rift would exacerbate this dire situation. It is time, therefore, for the two sides to work out their differences quickly and quietly.

Shuja Nawaz is director of the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center. The essay originally appeared at Foreign Affairs.